Clinical quality registries have never been more important, yet the question is whether they are breaking barriers or reinforcing silos.

Access and affordability remain the two biggest challenges in Australian healthcare.

The promise of AI is to personalise care, but are we really prepared for digital disruption? Do we have the tools we need?

Clinical quality registries (CQRs) have never been more important, yet the question is whether they are breaking barriers or reinforcing silos.

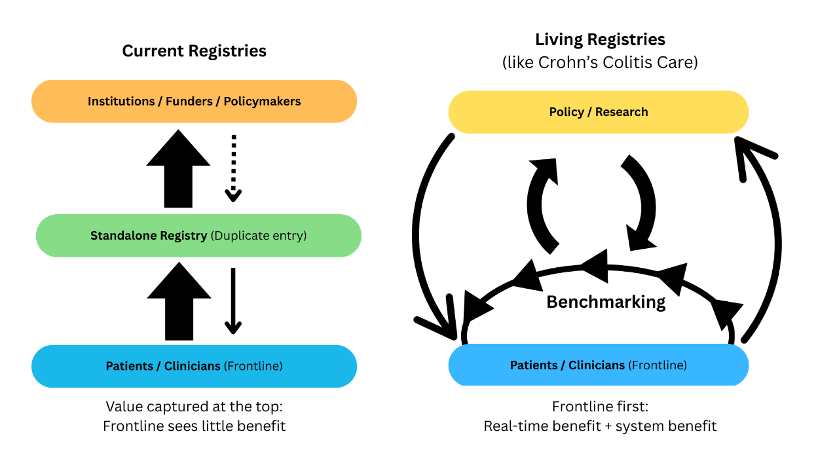

Patients deserve to be more than passengers in their own care; they must be active participants, supported by systems that deliver real-time value at the point of care. Instead of driving integration and improvement, many registries add burden without feedback, fragmenting care further.

It is time to reimagine their role and that means a deep dive into what they deliver, where they fall short, and what the future needs to look like to fully harness the power they offer for our entire health system.

WHO DO REGISTRIES REALLY SERVE?

Despite growing recognition of the increasing complexity and cost of healthcare delivery, meaningful reform remains elusive. Health systems continue to underinvest in early intervention, coordinated care, or the development of truly personalised models that reflect the full complexity of each individual’s journey. The result is care that is reactive, fragmented, and poorly aligned with the needs of those living with chronic illness and/or multi-morbidity.

This fragmentation is fuelled by silos, as our health system is divided into multiple verticals that rarely connect. Patients do not live their lives in neat single-disease categories or funding streams, nor do they live within large healthcare facilities. Most care is (and should be) planned and delivered proactively in ambulatory and community settings. For conditions like IBD, this is especially true.

Over a lifetime, the majority of costs sit in outpatient care, PBS therapies, outpatient diagnostics (radiology, endoscopy, blood work), and ongoing specialist management rather than in acute hospital episodes. Yet registry design and funding often privilege large institutions, leaving the settings where patients spend most of their lives poorly documented or supported. These silos slow innovation, deepen inequities, and make it harder for patients to navigate care.

Clinical quality registries were intended to help create visibility of care and outcomes across silos, to bridge the gap between research and practice, to drive improvement and quality of care. Yet, in practice, they have too often become silos themselves.

Disconnected from the point of care by being based in organisations removed from care delivery and dependent on retrospective reporting, they add administrative burden without delivering meaningful feedback to patients or clinicians. A tool designed to integrate across the system has, paradoxically, reinforced its fragmentation.

The concentration problem

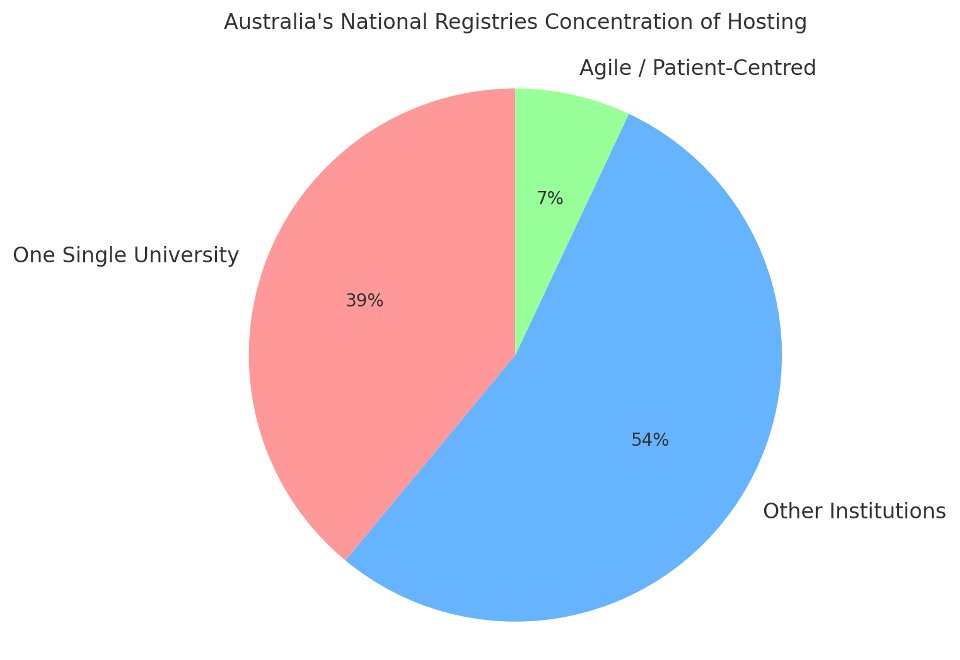

The current funding model heavily favours organisations with existing infrastructure, scale, and grant-management capacity. These large, well-established entities fit neatly into current program requirements and, unsurprisingly, dominate the landscape.

This is not their fault. They are simply playing within the rules as they currently exist. The way CQRs are currently endorsed and funded thus creates a self-perpetuating systemic bias in favour of established institutions. Funding follows scale and prestige, not innovation or impact, leaving smaller, more agile organisations excluded.

Moreover, due to the system design for CQR funding, another concerning outcome is a lack of diversity in who builds and manages them. Instead of a healthy mix of academic, clinical, and consumer-driven models, most funding flows to a small cluster of traditional providers. (see table: Commonwealth invested registries )

| Registry (CQR) | Host / Operator (how described publicly) | Host type | Evidence |

| Australasian Pelvic Floor Procedure Registry (APFPR) | Managed by Monash University | University | APFPR site and Monash registry page state “managed by Monash University.” (Health.gov.au) (apfpr.org.au) |

| Australasian Shunt Registry | Established and run by the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia (NSA) | Professional society | NSA annual report and ACSQHC register listing. (NSA Australia) |

| Australia–New Zealand Trauma Registry (ANZTR / ATR) | Custodian: Alfred Health (NTRI); Database management & reporting: Monash University (DEPM/SPHPM) | Hospital (custodian) + University (operations) | NTRI page and Monash page. (National Trauma Research Institute) |

| Australian & New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR) | Hosted by Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA) & NZ Orthopaedic Association | Independent institute + Professional college | ANZHFR “About” page. (anzhfr.org) |

| Australian Breast Device Registry (ABDR) | Managed by Monash University | University | ABDR site; plastics society page. (abdr.org.au) |

| Australian Cystic Fibrosis Data Registry (ACFDR) | Funded & data custodian: Cystic Fibrosis Australia; Management company: Monash (since 2016) | Consumer org (custodian) + University (management) | CFA registry page and Monash registry page. (cysticfibrosis.org.au) |

| Australian Dementia Network (ADNeT) Registry | Managed by Monash University (within multi-institution ADNeT) | University (lead operations) | ADNeT pages and 2024/2025 reports. (Australian Dementia Network) |

| Australian Spine Registry (ASR) | Initiative of Spine Society of Australia; Managed by Monash University | Professional society + University (management) | SSA & Monash pages; ASR brochure. (Spine Society Aus) |

| Australian Diabetes Clinical Quality Registry (ADCQR) | Managed/hosted by Monash University; funded by DoHDA; supported by NADC/ADS | University | ADCQR site & data dictionary; NADC materials. (Monash University) |

| National Cardiac Registry (NCR) | Operations contracted to Monash University (CCRET) | University (operations) | NCR “Registry Operations” page; NCR 2024 report. (nationalcardiacregistry.org.au) |

| Australian & New Zealand Intensive Care Registry (ANZICS CORE) | Hosted/operated by ANZICS (professional society) | Professional society | ANZICS site (CORE registries). (ANZICS) |

| Australian Stroke Clinical Registry (AuSCR) | Consortium: The Florey (data custodian), ANZ Stroke Organisation, Stroke Foundation, Monash University | Research institute + NGOs + University | ACSQHC listing and AuSCR site. (Safety and Quality) |

Concentrating funding in such a limited group distorts the health ecosystem further by effectively turning those organisations into de facto setters of health policy and funding priorities. By controlling which data are collected, how they are analysed, what findings are published and how the reports are framed, they shape the evidence base that informs government decisions.

Yet these institutions are not representative of the broader health system. Consumer-led organisations, smaller innovators, and most importantly clinicians are effectively excluded from setting the agenda. The result is a policy environment shaped more by institutional survival than by patient need.

When Registries Become About Institutional Relevance

The original purpose of CQRs clinical registries was to improve patient care and outcomes. Yet, over time, the CQR program has also become a mechanism for institutions to demonstrate their own relevance. Large universities and hospital-based centres host registries not necessarily because they are the most innovative or impactful for patients, but because registries strengthen their institutional positioning.

For governments, funding these incumbents looks safe. A registry housed in a major university or hospital brings credibility and gives the appearance of stability. For institutions, hosting a registry signals authority, secures ongoing investment, and generates a steady stream of academic outputs. Publications and prestige flow upward, reinforcing the institution’s status as the “national reference point.”

The problem is that patients often see little immediate benefit. Improvements emerge only after years of retrospective analysis, while the immediate gains flow to institutions in the form of funding, visibility, and credibility. The system has drifted from being about real-time improvements in care to being about institutional survival and relevance in a competitive funding landscape.

The innovation deficit

Here is the uncomfortable truth: none of the federally funded registries measure care in real-time nor do they provide a real-time feedback loop back into the point of care.

The ACSQHC has consistently highlighted the need for registries to enable timely and actionable insights. Yet what we see on the ground are models that require double data entry into standalone platforms, disconnected from the point of care. At best, dashboards refresh overnight but data are not guaranteed to update; more often, registries publish annual reports or lagging indicators months after the fact.

These registries are important for retrospective benchmarking and research. But they are not dynamic. They do not inform today’s consultation. They are systems of accountability rather than catalysts for real time improvement.

Why “daily dashboards” are not real-time

The Australian Stroke Clinical Registry (AuSCR) is often held up as a national exemplar because it provides dashboards that refresh daily. Yet this is not true real-time feedback. Data are manually entered into a standalone platform separate from the EMR. Dashboards update overnight, but only if staff have kept up with data entry. Accuracy and currency depend entirely on local resourcing to ensure compliance, with verification occurring retrospectively through audits and data validation studies.

Consequently, dashboards can lag days or weeks behind clinical reality. By contrast, platforms like CCCare eliminate double entry, updating instantly within the consultation, and providing a closed feedback loop to improve care in the moment. IBD-PERFECT (the open reporting arm of CCCare), is now also providing actionable insights to clinicians to assist them manage data completion themselves continuously in real time. This benchmarking and continuous improvement initiative is an Australian (and possibly global) first and shows what well designed registries and modern data architecture is capable of.

Why universities cannot deliver real-time care improvement

Universities do not deliver care. Their registries sit apart from the point of care, structurally siloed from hospitals and patients. Rather than breaking down barriers, this model reinforces them.

An unintended consequence is a significant opportunity cost for care sites. Clinicians and staff must maintain registry data on top of their usual workload, with no dedicated funding to support it. Time and resources are diverted away from patients, adding cost and administrative burden with little immediate return.

While university-led registries generate valuable research outputs, they are poorly positioned to drive real-time outcomes at the bedside. Improvements emerge only after years of audit cycles, quality meetings, and retrospective benchmarking. They are bolted on rather than built in – meaning patients waiting in front of their clinician see little direct benefit.

By contrast, registries embedded in care delivery – like CCCare – are built into the consultation itself. Data are captured once, structured and dynamic, and immediately feed back to both patient and clinician. This is how registries should function if the goal is to improve outcomes in real time, not just publish reports after the fact.

Who Do Registries Really Serve?

Today’s registries seem confused about who their real consumers and beneficiaries are. Instead of delivering value to patients and clinicians, they are built to satisfy institutional reporting and funding requirements. Data flow upward to policymakers and academics, while the people at the frontline see little immediate return.

A reset is needed. Living registries put patients and clinicians back at the centre: data captured once, used instantly to guide care, and still available to inform research, benchmarking, and policy. This is how registries could and should deliver both real-time impact and long-term system benefit.

THE EQUITY GAP AND THE VICIOUS CYCLE OF INVISIBILITY

Here we look at how visibility or lack thereof, shapes health investment, and why high-burden conditions like IBD remain unfunded and overlooked.

The equity gap

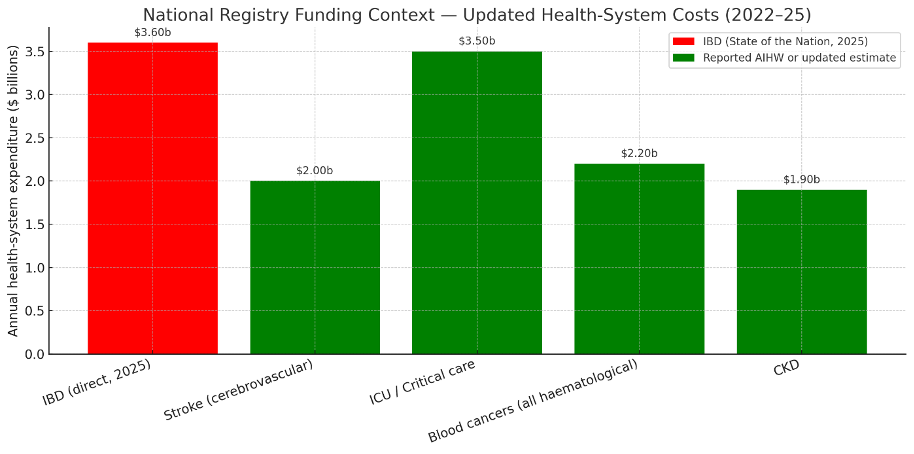

Despite a $3.6 billion annual health-system cost (Crohn’s & Colitis Australia, State of the Nation, 2025), IBD is buried within “other gastrointestinal disorders” in national accounts and remains unfunded, while registries for other specific diseases with established institutional homes continue to receive Commonwealth support. This creates an equity gap where the most urgent needs are unmet, while the profile of, and investment in, established disease areas are further entrenched.

Again, this is not about blaming the diseases or institutions that currently receive funding. It is about recognising that we are not playing on a level field and the system does not actually reward innovation or respond to areas of greatest patient need.

The Paradox of Visibility

IBD is one of the most costly, complex, and under-recognised chronic conditions in Australia, affecting ~180,000 people currently, and projected to affect 1% of the population by 2025. It disproportionately affects young people in their most productive years, carries high rates of hospitalisation, and leads to significant loss of workforce participation. Yet in the architecture of government funding, IBD remains largely invisible.

Other conditions (like stroke, hip fracture, cystic fibrosis, breast devices) have institutional champions and government-funded registries that reinforce their profile. Data flows upward to policymakers, strengthening the case for continued investment. IBD, by contrast, lacks a government-funded registry. Without the ability to generate official national data, it is overlooked in funding cycles and policy debates, no matter how great the need.

Why IBD is invisible in the data

- IBD care is predominantly ambulatory and federally funded:

- Biologics and immunomodulators → PBS

- Specialist & GP visits → MBS

- Pathology, imaging, stoma products → mixed federal programs

- These costs are fragmented across Commonwealth programs rather than hospital budgets.

- Stroke, CKD, ICU care are dominated by inpatient episodes funded by state hospital budgets, which are well tracked in AIHW expenditure tables.

- IBD costs in a hospital budgets include a significant proportion of avoidable hospitalisations and surgeries (up to 50% on some estimates) – costs that a registry could help prevent through earlier intervention and coordinated care.

The result is a visibility bias: conditions whose costs are centralised and easily captured appear larger and attract registry investment. IBD, by contrast, is dominated by dispersed ambulatory costs and split federal programs, making its true $3.6b direct costs burden effectively invisible in official accounts, noting that the real cost of IBD to society is even higher – estimated at $7.8b in 2025 alone (SOTN).

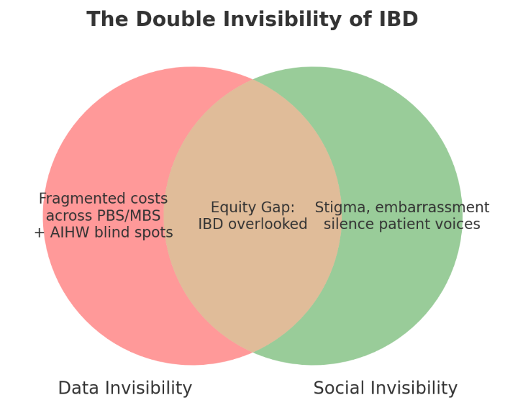

Why IBD is invisible in society This invisibility is compounded by stigma. Symptoms such as rectal bleeding, diarrhoea, incontinence, and the presence of a stoma are often stigmatised. Many patients feel embarrassment or reluctance to speak openly about their disease. This reduces advocacy pressure, public recognition, and political priority – reinforcing IBD’s invisibility compared to more socially “acceptable” conditions.

The cycle reinforcing invisibility

Together, these factors compound to make IBD one of the most overlooked chronic diseases in Australia. Hidden both in the data and in public discourse, without visibility, equity is impossible.

This creates a vicious cycle: no registry means no visibility; no visibility means no funding; and no funding means continued invisibility. Ironically, the very tool that could break this cycle – a clinical registry – is what IBD has been denied.

Platforms like CCCare demonstrate what is possible: a patient- and clinician-centric registry that captures data in real time, identifies unmet needs, and provides evidence of cost and inequity. It makes IBD visible not only to policymakers but also to clinicians and patients at the point of care. If universal healthcare and equity is truly the goal, IBD cannot remain invisible

What’s possible

Platforms like CCCare show another way. Embedded at the point of care, CCCare captures structured data once, feeds it back instantly to patients and clinicians, and highlights unmet needs in real time. At the same time, it generates the evidence policymakers require.

This is how registries should work: improving care today, while building the evidence base for tomorrow. If equity is the goal, IBD cannot remain invisible.

The invisibility of IBD is not inevitable – it’s structural. And it can be changed.

WHAT HAVE REGISTRIES DELIVERED – AND WHAT COMES NEXT?

We reflect on the impact of registries so far, the systemic biases that shape them, and a future model that puts patients and clinicians at the centre.

The promise and the reality

Funded registries have delivered important benefits — but slowly.

To be fair, some funded registries have already delivered important benefits.

- Stroke (AuSCR): Improved hospital adherence to secondary prevention, discharge planning, and rehab referrals – but only after 1-3 years of participation.

- Hip Fracture (ANZHFR): Faster time to surgery, better mobilisation, and lower 30-day mortality – but measurable improvements took 2-4 years.

- Cystic Fibrosis (ACFDR): Decades of data show improved survival; multi-year evidence supported access to life-changing new therapies.

- Breast Device Registry (ABDR): Identified unsafe implants and triggered recalls – but only after years of accumulated data.

Others (spine, trauma, dementia, pelvic floor, cardiac) are still building data sets, with outcome impacts years away. The pattern is clear: current registries deliver improvements through long audit and feedback cycles, measured in years or decades. None deliver immediate change at the point of care.

Reinventing the wheel

The Commonwealth is now investing in new programs to add patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and data-linkage capacity into existing registries. Yet platforms like CCCare already deliver these functions, built in from day one, with development costs already paid by a nimble NFP, making it great value for CQR funding!

Ironically additional funding is now being given to existing registries to build capabilities that already exist in unfunded, consumer-driven registries. Rather than duplicating effort, the Commonwealth should support and scale proven innovations that are working today.

Time to reset the agenda

Australia needs to move beyond retrospective, audit-style registries and toward real-time, patient- and clinician-centric systems. If we are serious about equity, innovation, and value-based healthcare, we need to:

- Open the field: Ensure registry funding is accessible to consumer-led and hybrid governance models, not just large incumbents.

- Prioritise innovation: Support real-time, dynamic platforms that integrate with clinical care, rather than static databases.

- Embed equity: Direct funding towards high-burden, under-served conditions like IBD where unmet need is well documented.

- Redefine exemplars: Stop describing overnight dashboards as “real-time.” True exemplars eliminate double entry and close the loop at the point of care.

CCCare: Reimagining Registries and Connected Care

Australia has invested in more than 100 registries – yet the vast majority are concentrated in large institutions, built around retrospective data entry and long audit cycles. Nearly half sit within a single university. These registries have value, but they are not built to deliver real-time improvements in care.

There are also a small number of clinician- or consumer-initiated registries. They show that alternatives outside the dominant institutional model are possible. But none match the scale or impact of CCCare, which goes further than any other registry in Australia.

CCCare is different because it was designed from the ground up as an integrated ecosystem:

- Embedded in care: Data are captured once during the consultation itself, eliminating duplication.

- Real-time value: Patients and clinicians see insights instantly, not years later in reports.

- Consumer empowerment: Patients contribute their own data, set consent preferences, and remain active participants.

- Governance that serves patients: A not-for-profit model with strong clinician and consumer leadership, focused on improving care rather than institutional prestige.

By not yet funding CCCare (declined funding 2024 and 2025), government is forgoing the opportunity to back a world-leading model that already demonstrates how registries can transform care, equity, and system performance. The opportunity cost is profound:

- For patients, years of avoidable hospitalisations, inequities, and delayed access to new therapies.

- For clinicians, extra workload and lost time duplicating data entry.

- For government, paying twice – once to maintain slow, retrospective systems, and again to retrofit features already proven in CCCare.

Importantly, CCCare is not just a proof of concept , it is already being deployed at scale to deliver a new data product to enhance care – IBD-PERFECT, the first national benchmarking framework for IBD. Beyond benchmarking, CCCare has already demonstrated a significant return on investment. By reducing avoidable events such as hospitalisations and surgeries by at least 12%, the platform has the potential to deliver hundreds of millions of dollars in health system savings over timewhile simultaneously improving quality of life for patients.

Born out of the State of the Nation report, IBD-PERFECT shows how CCCare can be used to deliver agreed standards of care, provide transparent public dashboards, and directly address the priorities identified by patients and clinicians. It demonstrates that a patient- and clinician-centred platform can both improve care in the consultation and generate the national evidence needed for equity, policy, and funding reform. In doing so, it closes the loop between frontline care, national standards, and system transformation.

CCCare and IBD-PERFECT: An Exemplar for the Government’s Digital Health Blueprint

At its core, IBD-PERFECT is powered by CCCare – a platform that does more than any traditional registry. CCCare integrates clinical data, consumer-entered data, and registry data into a single connected ecosystem. This makes it not only a benchmark for IBD but also a living demonstration of how the Health Connect Strategy can be operationalised cost-effectively, today.

Alignment with Health Connect Strategic Goals

- Information Access: Clinicians and consumers have the right information at the right time, within the consultation.

- Consumer-Centric: Patients contribute their own data, set consent preferences, and share seamlessly with care teams.

- Digital Transformation: A cloud-based, standards-ready platform designed for national scalability and interoperability (HL7 FHIR, consumer-mediated exchange).

- Trusted and Secure: Advanced consent frameworks, de-identification, and ethical governance ensure privacy and trust.

Why CCCare is an Exemplar

- Linked Data at Scale:

- Connects EMR, pathology, and consumer-generated health data within a federated model.

- Demonstrates interoperability patterns (consumer-mediated exchange, directed referrals, discovered data exchange).

- When combined with PBS/MBS, enables government to:

- Identify unmet need at a system level.

- Conduct post-market surveillance of medicines and devices by linking prescribing and utilisation with outcomes.

- Real-World Evidence in Real Time:

- Continuous capture of consumer and clinician-entered data produces live RWE streams.

- National benchmarking (IBD-PERFECT) and dashboards drive safety and quality.

- Goes beyond value-based care to support personalised prevention and intervention, measuring outcomes at the individual level.

- Research and AI Acceleration:

- Provides ethically governed, de-identified datasets for research and industry R&D.

- Enables AI-driven prediction and personalised treatment pathways.

- Facilitates clinical trial recruitment by matching patients in real time across hospitals and the consumer app.

- Impact Across the System:

- Funding: Enables value-based models and sharper government insights when linked with PBS/MBS.

- Prevention: Supports individualised prevention, overcoming the bluntness of population programs.

- Research: Unlocks data for discovery and streamlines trial recruitment.

- AI: Provides the foundation for predictive and equitable healthcare.

A Call to Action: Fund Real-Time Registries

The journey comes full circle. The State of the Nation report called for urgent action to address inequities in IBD and to establish national standards of care. Traditional registry models might take years to respond – if at all. But with CCCare underpinning IBD-PERFECT, we already have a living framework that can set standards, measure outcomes, and deliver equity in real time. What was once only an aspiration is now operational. It proves that registries can close the gap between vision and delivery – not years down the line, but today.

The ACSQHC has rightly set an ambitious vision for registries to drive quality improvement. But the current funding and governance model falls short, concentrating support in a narrow set of incumbents and perpetuating retrospective reporting.

If Australia wants to be a global leader, we must break free from this retrospective, centralised mindset. Patients deserve more than annual reports and lagging indicators. They deserve registries that work with them, for them, in real time.

We no longer need to imagine what better looks like because it already exists. Government could act now to end years of inertia and deliver the care patients deserve, in real time. If they choose not to, one would have to ask, “Why not?”

Professor Jane M. Andrews is an internationally recognised Key Opinion Leader in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). She chairs Crohn’s Colitis Cure (CCCure), co-chairs the global IBD research consortium GLIDE, and her expertise spans clinical trials, translational research, and policy, making her a leading voice in improving outcomes for people living with IBD.

Bill Petch is CEO of CCCure and Chair of the Prince of Wales Hospital Foundation. He is a recognised leader in healthcare innovation and organisational transformation, with a track record in developing national strategies, patient-centred registries, and system reforms that improve equity and outcomes.

References available on request, contact amanda@medicalrepublic.com.au