Local immune effector cell-associated toxicity syndrome is a frequent, but mild effect of the treatment, researchers claim.

A new form of CAR T cell-associated toxicity has been identified, leading researchers to call for greater awareness of organ-specific changes in patients with autoimmune disease.

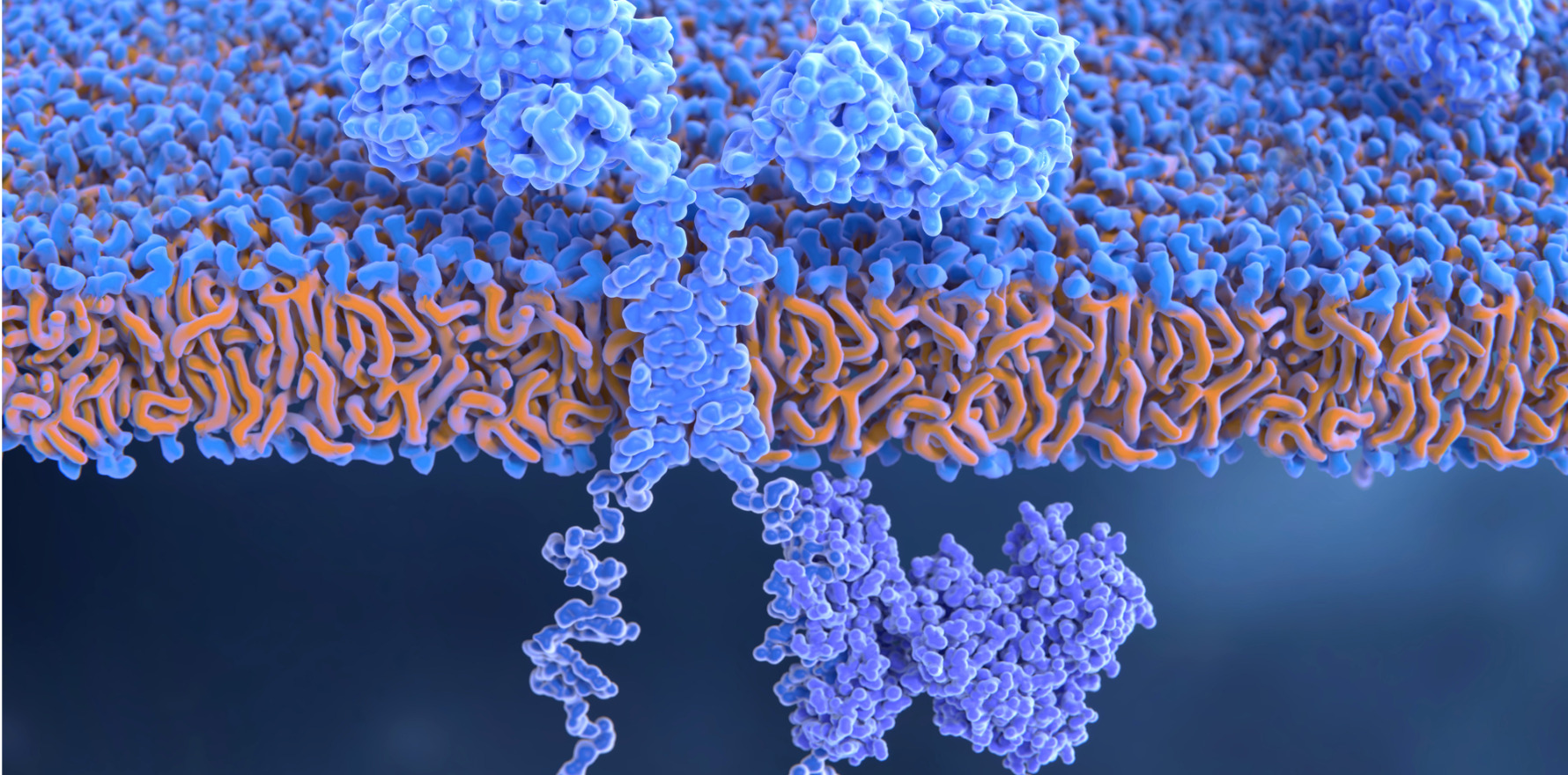

The implementation of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy has been a boon for several autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus due to the treatment’s ability to deplete B cells much deeper within affected tissue.

Now, a group of German researchers have identified a new side effect of the treatment they have dubbed local immune effector cell-associated toxicity syndrome, or LICATS.

“LICATS is a local and self-limited impairment of organ function that occurs after CAR T-cell treatment and follows the disease-specific organ involvement before treatment,” the researchers wrote in The Lancet Rheumatology.

Thirty-nine patients (20 with SLE, 13 with systemic sclerosis and six with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy) who received CD19-targeting CAR T therapy in one of two German hospitals who experienced organ-specific reactions were included in this retrospective observational study. Most patients were female (64%), and the median age of included patients was 36 years.

Of these 39 patients, 30 (77%) were deemed to be affected by LICATS, with the greatest proportion of patients experiencing LICATS seen in the SLE cohort (80%) compared to the systemic sclerosis (77%) and IIM (67) groups.

Half of the patients experienced only one LICATS manifestation, while the other half experienced more than one event. LICATS manifestations appeared a median of 10 fays after the CAR T cell infusion and lasted for a median of 11 days (half of the events occurred within two weeks of CAR T cell treatment).

The three most frequently observed LICATS responses were skin rashes (35%), decreased renal function or proteinuria (22%) and musculoskeletal manifestations (19%). Interestingly, the LICATS responses primarily occurred in organs previously affected by the specific autoimmune disease.

“Patients with SLE showed preferential involvement of the skin and the kidneys, while patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy or systemic sclerosis with muscle involvement showed transient elevations of creatinine kinase… suggesting a tropism of event brought about by CAR T-cell mediated B-cell killing,” the authors noted.

The majority of LICATS were mild and either resolved spontaneously (65%) or following a short course of glucocorticoids (30%).

The researchers were unsure of the mechanism underlying LICATS but put forward a number of potential explanations.

“These self-limited inflammatory events could be based on the action of the CAR T cell itself, following the local release of cytokines or target cell killing; triggered by autoreactive T cells, which are re-infused as non-transduced T cells and expand next to the CAR T cells in the patient; or by the re-emerging immune cells following lymphodepletion, including, but not limited to, effects of fludarabine on myeloid cells and regulatory T cells,” they wrote.

However, the researchers were more confident that the LICATS responses were a separate phenomenon to cytokine release syndrome.

“LICATS seems to be different from CRS, which typically starts a median of 2 days after CAR T-cell infusion and is associated with signs of systemic inflammation such as fever, chills and elevation of acute phase reactants (especially IL-6), indicating the systemic inflammatory nature of CRS. In contrast, LICATS is localised, shows no IL-6 elevation, is later in its onset, and is treated with lower-dose glucocorticoids, if needed,” they highlighted.

Related

The researchers also offered several reasons why LICATS was different to a disease flare.

“First, most LICATS did not require any treatment and disappeared spontaneously. Second, most LICATS occurred during the CAR T-cell peak, suggesting association with CAR T-cell therapy rather than the underlying disease,” they wrote.

“Third, LICATS occurred when there was still a potential influence of conditioning treatment, making a flare of autoimmune disease unlikely. Fourth, no signs of enhanced autoimmunity (C3 or C4 consumption, increase of autoantibodies) were observed with LICATS. Therefore, LICATS should not trigger reintroduction of continuous immunosuppressive treatment (e.g., T-cell inhibition) for autoimmune disease.”

Regardless of the cause, the researchers called for greater awareness of LICATS moving forward.

“Knowledge about LICATS is crucial to prevent misinterpretation and unnecessary immunosuppression. We therefore suggest LICATS as a new adverse event that should be assessed in future CAR T-cell trials in autoimmune disease,” they concluded.

“Such prospective assessment of LICATS in CAR T-cell trials will help to assess the prevalence of this toxicity among different cellular interventions in autoimmune disease and better characterise its management and outcome.”